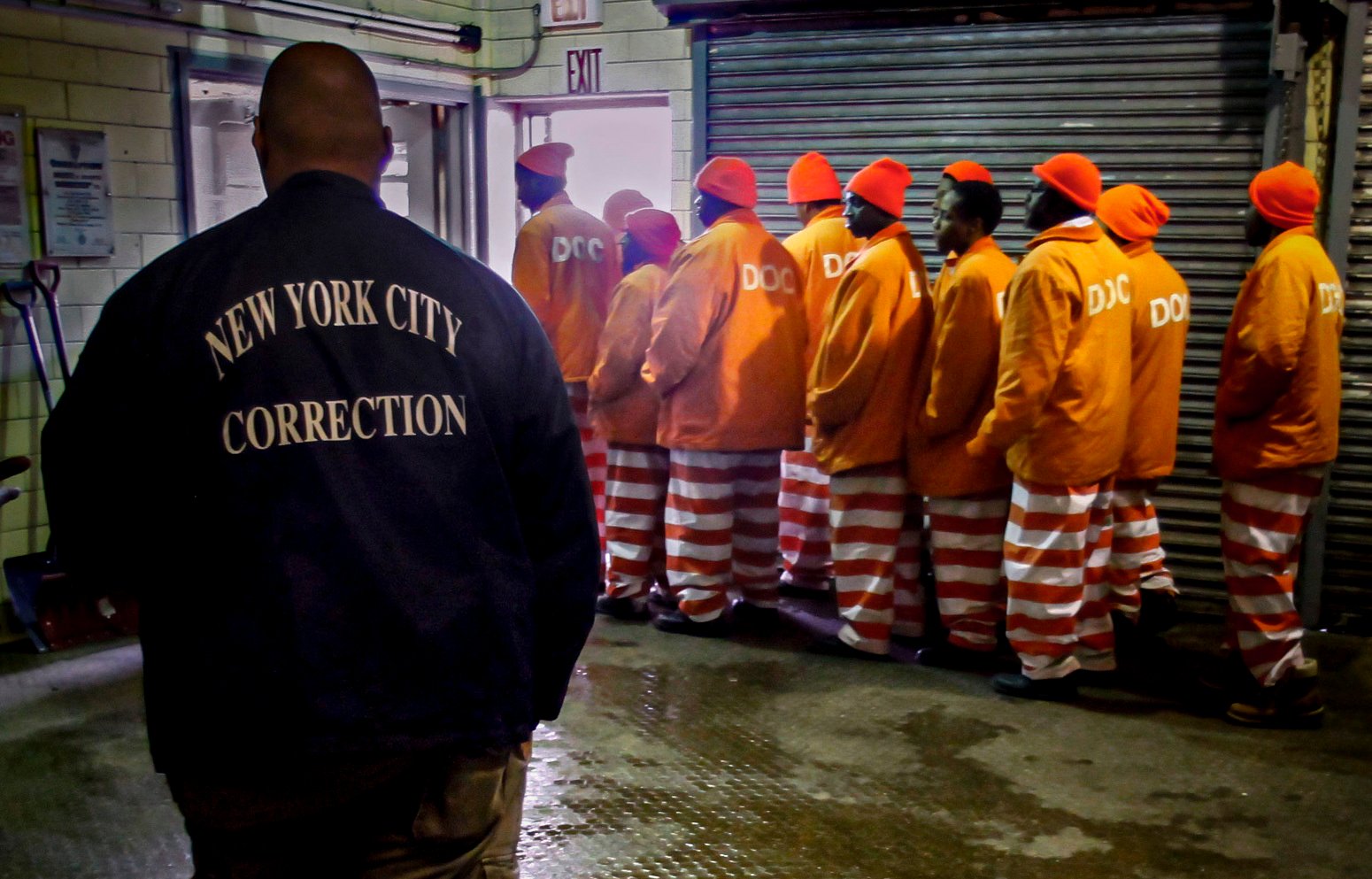

RIKER'S ISLAND, N.Y. (CN) — Detainees at New York City’s most notorious jail complex live in conditions that, well before they stand trial, can result in a death sentence.

DaShawn Carter died by suicide last weekend, just two days after he was transferred to Rikers from a mental health facility.

“He had mental health issues, and that all by itself means there’s a human who’s crying for help and needs to be heard,” said Kevin Sylvan, the lawyer appointed by the court to represent Carter. “And tragically, like so many others, he doesn’t get heard the right way, the right time, or under the right circumstances.”

Carter is one of four people who died in custody this year alone at Rikers Island where filthy conditions, crumbling facilities and understaffing give way to rampant violence, injuries and illnesses. Medical care is insufficient. Correction officers are assaulted by the thousands. Advocates and government officials agree the situation is dire, but they clash on how to turn it around as pressure mounts to implement serious reforms before the facility is scheduled to be shut down in 2027.

Facing robbery and burglary charges, Carter had been set to appear in court on May 18. He had yet to meet with his attorney, Sylvan, who first learned about Carter's death from the media. The city’s Department of Correction reached out to him on Monday, two days after Carter was found slumped over near his bed.

Sylvan said the 25-year-old had been homeless and given few opportunities while detained to speak with family.

“This, of course, is a population that gets less attention than others in general in the first place,” Sylvan said. "The situation at Rikers exacerbates it, as does, naturally, Covid and everything associated with that.”

The rate of self-injury among detainees doubled during the first summer of the pandemic, and hit a five-hear high in 2021, The City reported.

Sylvan did not speculate as to the specific circumstances surrounding Carter’s death.

In each of the three other deaths at the facility in 2022, gaps in staffing and supervision played a part, according to a report released this week by the Board of Correction, which regulates jail conditions.

In March 2022, Herman Diaz, 52, died after a lag in medical attention when he choked while eating an orange. Other detainees tried to help Diaz, using the Heimlich maneuver, turning him on his side, and trying to get a correction officer's attention. They then physically carried Diaz to the clinic at the facility's Eric M. Taylor Center. No officers gave Diaz first aid.

Another detainee, the 48-year-old George Pagan, spent days lying in bed or on the floor leading up to his death. He appeared weak, barely ate, and “regularly urinated, defecated, and vomited on himself,” the report explains. Again, other detainees came to his aid, bringing him food and drink. It took more than 30 minutes for a medical team to check in.

Detainees may spend a week in a cell with 40 men — a holding area where they are meant to remain for just a day — and go two days without food, attorney Morris Shamuil told Courthouse News. It was in that cell that one client witnessed someone try to hang himself.

After officers responded, Shamuil said, “they came in and they cut him down, and just put him down in the cell and left again.”

Like many others, Shamuil says staffing issues are behind those incidents. “If they had more staff they’d be able to spread people out, they would be able to give more individual attention to people who need it,” he said. “If you have one officer for every 50 inmates, you can’t. You don’t have the manpower.”