This article is part of the NBC News Justice for All series.

ANGOLA, La. — His name was George Del Vecchio. On Nov. 22, 1995, I watched from behind a window at Illinois’ Stateville Correctional Center as Del Vecchio took his last breath. He was executed for the murder of a young boy 18 years earlier. I was a media witness to that execution.

As the other witnesses and I were escorted out of the prison that dark early morning, I began to wonder — was the world any safer because George Del Vecchio was now dead?

It was the first time I recall deeply considering our system of crime and punishment. Was it supposed to be only about punishment? Retribution? Or is the goal to make us safer? It was the kind of conversation that didn’t get much traction in the “get tough on crime” ‘90s. But nonetheless, it stayed with me.

This April, nearly 24 years after coming face to face with our system’s ultimate and irreversible penalty, I tackled that question again from the only place that made sense: inside a prison. I embedded with inmates at the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola.

Watch the full "Dateline NBC" Life Inside episode here

During a particularly dark period in the '60s, it earned the nickname “the deadliest prison in the South.” Today Angola is the largest maximum-security prison in the country in a state with a higher rate of incarceration than nearly any place on earth. To see inside Angola is to see mass incarceration in its extreme.

For two nights I slept and to a limited extent lived like an inmate in Angola, housed in a tiny cell in the same facility where the most difficult inmates are kept, and chillingly just a few steps away from death row. Journalism thrives on access. To understand the issues of criminal justice reform that are now riding atop a bipartisan wave, it was important to me to get close. And so I did.

The open stainless steel toilet, metal frame bed and brick walls are just like you’ve seen on countless TV shows and movies. The talking goes on late into the night, and the toilets flush often and loudly. Food is delivered on a tray through a horizontal slot in the door.

The only thing different about my cell were the cameras my “Dateline NBC” crew installed, which rolled constantly except when nature called. The men on my tier were only allowed out of their cells for one hour a day, and just three hours a week in an outdoor courtyard.

NBC News and USA Today are taking an in-depth look at criminal justice reform and mass incarceration in America. To read USA Today's interview with Lester Holt on his reporting from inside Angola, click here.

My immediate neighbor, who was serving time for murder, told me he hadn’t been outdoors in four years, preferring to stay inside. I, however, spent daylight hours outside my cell traveling across the sprawling prison grounds, meeting inmates and staff and trying to grasp the workings of a society that is foreign to most of us.

We chose Angola because it symbolized a reckoning underway for the American criminal justice system. In recent years, Louisiana has gone from having the highest incarceration rate in the country to No. 2. (Oklahoma is now No. 1.)

“We had the highest incarceration rate in the nation for the last couple of decades, but our crime rate wasn’t any better for it,” Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, told me. “The recidivism rate wasn’t better.” In 2017, in response to that conclusion, Louisiana’s legislature passed a series of reforms that led to the early release of many nonviolent offenders, reducing its prison population.

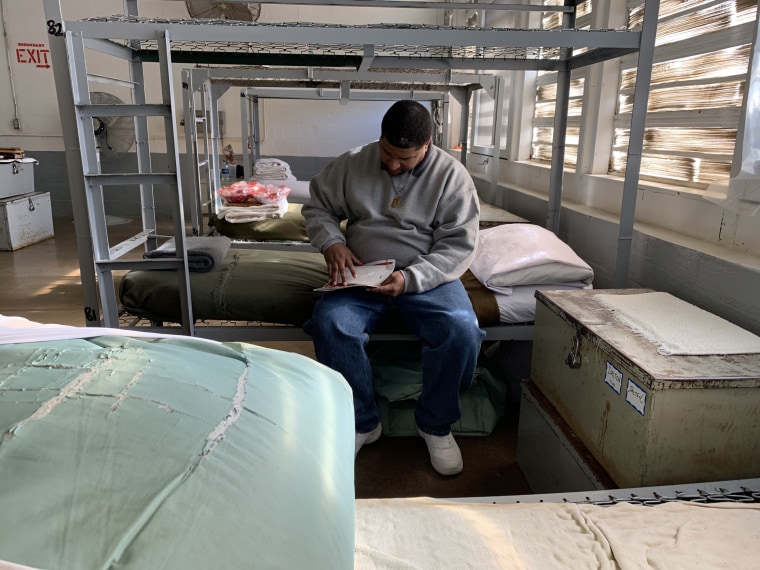

Most of Angola’s 5,500 inmates are serving sentences of life without parole. Nearly everyone had been convicted of murder. Yet our access to inmates and corrections officers was virtually unrestricted. In fact, there were moments I found myself alone with inmates. I never felt threatened, but my senses were on full alert. My cell was the only place I fully let my guard down.

I felt no apprehension, however, speaking with Sammie Robinson. Robinson is 83 and has been in prison since 1953, well before I was born. I asked him if he wanted to go home, and he replied, “Ya, I want to go home.” I thought to myself, “After 66 years isn’t this your home?” It’s hard to imagine Robinson posing a threat to society — more than six decades have passed since he killed a fellow inmate while behind bars for an aggravated rape charge that was later thrown out — but the fact is, he and most of the men I met at Angola will most likely die inside its walls. There’s a reason they call it “life in prison.”

Robinson is just one of the geriatric inmates I met who are part of a growing older demographic in American prisons. Many are violent offenders, yet many of them committed their crimes as teenagers. “Juvenile lifers,” as they are known, are now a major issue in criminal justice reform efforts and one I spent a lot of time exploring and struggling with during my three days and two nights at Angola.

To a person, they told me that they had changed and that they are not the wild kids they were when they came to Angola. All of them want a second chance. But who and what do you believe? As I wrote in my journal back in my cell the first night, “You never know when you’re being B.S.-ed.”

During my visit I learned a lot about the value of hope, like the excitement generated when incarcerated men faced the parole board. I was surprised to see corrections officers quietly rooting for prisoners they thought particularly deserving of release. Some even confided their disappointment when those inmates were turned down for parole, contrary to the adversarial relationship that exists between officers and inmates.

I was equally surprised to hear from some of those officers that removing the possibility of parole makes prison more dangerous for all. They told me the introduction of programs and learning opportunities for prisoners, especially lifers, has improved conditions at Angola and made their own lives appreciably better.

At the prison’s automobile repair program I met a lifer by the name of John Sheehan, who teaches job skills to men who are nearing the end of their sentences. Sheehan will never leave Angola, but he tells me teaching others has given him validation.

“You know that you’ve done something, and your life is worthwhile,” he told me.

On the outside, criminal justice reforms are often weighed against hard data points on recidivism risk and crime. Living on the inside, I found it to be a complex world filled with contradictions and still rooted in punishment but aspiring to be a place of rehabilitation. A work in progress that is now getting the attention it demands.