Judge says prosecutor in Navy bribes trial committed ‘flagrant misconduct,’ but won’t throw out case

Federal judge turns aside defense contention that misconduct tainted entire trial of five former Seventh Fleet officers in ‘Fat Leonard’ case

A San Diego federal judge ruled Wednesday that the lead federal prosecutor in the “Fat Leonard” bribery and fraud trial of five former Navy officers committed “flagrant misconduct” by withholding information from defense lawyers — but concluded the behavior was not enough to dismiss the case.

U.S. District Judge Janis Sammartino also found that, in three other instances where the defense lawyers had contended evidence helpful to their clients was withheld, prosecutors had not violated the legal rule requiring the government turn over information it has that could help a defendant.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Though she did not throw out the case as defense lawyers asked, Sammartino’s conclusion that Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Pletcher committed misconduct may cast a shadow over the 16-week trial that concluded on June 29 with a jury finding four of the defendants guilty of conspiracy to commit bribery, accepting bribes and wire fraud. The panel deadlocked on charges on a fifth defendant.

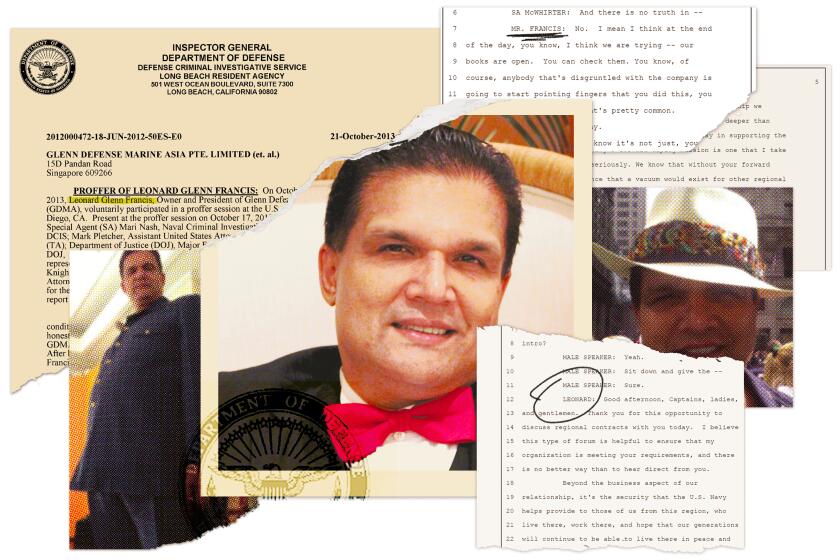

Former Capts. David Newland, James Dolan and David Lausman and former Cmdr. Mario Herrera face sentencing later this year stemming from their dealings with Singapore-based military contractor Leonard Glenn Francis, who was known by the nickname “Fat Leonard” because of his ample body composition.

The government contended that Francis bribed the officers with fancy meals, hotel stays, gifts and the services of prostitutes while they served with the Navy’s Seventh Fleet. In return they gave him classified information about ship movements and internal deliberations about port visits, and steered ships to ports across Asia where Francis’s company Glenn Defense Marine Asia controlled ship services.

Once in his ports, he wildly overcharged the government, eventually admitting to defrauding taxpayers out of at least $35 million.

Lausman was also convicted of obstruction of justice for destroying a computer hard drive with documents and emails from his time as the commanding officer of the aircraft carrier George Washington.

The jury deadlocked and reached no verdict on charges against former Rear Adm. Bruce Loveless. In a motion filed this week he is asking Sammartino to acquit him outright, a request the government is expected to contest. Prosecutors have not yet said if they plan to retry him.

The judge’s ruling came weeks after an extraordinary, mid-trial three-day long hearing in which the prosecutorial misconduct allegations were aired. Pletcher was put on the stand to testify about his decision not to tell defense lawyers that a prostitute who the government said had sex with Lausman at a wild party in May 2008, told federal agents she never had sex.

The case of “Fat Leonard” is the Navy’s worst corruption scandal in modern history. Here’s all the latest coverage of the ongoing investigations and court proceedings.

The woman, known as Ynah, told federal agents on March 4 and March 8 — just days after opening statements — that while she went to Lausman’s hotel room the night of the 2008 party, “nothing happened” and she slept on the room’s couch.

Agents had contacted her 14 years after the party to see if she was willing to come to the U.S. to testify, Sammartino wrote. She declined, but in a text message told the agents said she did not have sex with Lausman.

The agents told Pletcher about Ynah’s statement four times over the succeeding weeks and asked how they should write up the information in a report that would, normally, be turned over to the defense as federal court rules require. But each time Pletcher put them off, Sammartino wrote.

On April 20, Lausman’s lawyers filed a motion charging that the government was withholding information. Only then did the agents write a report— six weeks after the contact.

The defense attorneys said the information refuting the government charge that Lausman had sex with the prostitute violated the Brady Rule, which requires prosecutors to give defendants information and evidence that could show they are not guilty. It is named after a 1963 U.S. Supreme Court case which held that not doing so violates a defendant’s constitutional rights.

In her ruling Wednesday, Sammartino disagreed. She said that a defense investigator had contacted Ynah in February, and the woman told the investigator the same thing she would later tell federal agents.

Though Lasuman’s defense had the information, she said the government still had an obligation to disclose it — and to correct the statements made to the jury at the start of the trial.

In order to penalize the government for not doing that, Sammartino issued a special jury instruction. It told the panel there was no evidence that Lausman had received services of a prostitute, and they should ignore government statements to them that there was. She told them she was doing so because of the government’s “failure to timely disclose favorable evidence applicable to Mr. Lausman.”

That instruction was a sufficient penalty, she said in her ruling. And she said other defendants were not harmed by the late disclosure, because it came during the trial and they had time to use it to attack the case against their clients.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office declined to comment on the ruling, released late in the afternoon. Pletcher did not respond to a message left at his office. Robert Boyce, an attorney for Lausman, also declined to comment.

Defense lawyers also contended that the failure to disclose the Ynah information was so bad, it warranted complete dismissal of the entire case. They said the government had constructed a false narrative about “sex for secrets,” and Pletcher had made false statements to Sammartino about the agents’ contact with Ynah.

Sammartino ruled that there was other evidence that Francis had provided prostitutes to officers, and rejected the false narrative claim.

But she concluded that Pletcher’s “failure to disclose the Ynah contact amounted to flagrant misconduct” by the prosecutor.

“Federal agents approached Mr. Pletcher about the matter on four separate occasions, and he repeatedly rebuffed them,” Sammartino wrote. “It is clear to the Court that the information was willfully withheld from Defendants and misrepresented to the Court.”

However she said that the damage to the defense was “minimal and already remedied by the curative instruction” she gave to the jury. The misconduct was not enough, she said, for the “extreme remedy” of throwing out the case.

Sammartino also turned aside two other Brady claims by defense lawyers. One said the government did not disclose that federal agent Cordell DeLaPena had told other agents to offer $5,000 to prostitute witnesses in Asia to come to San Diego to testify.

She ruled that there was no violation because, again, the defense learned of this during the trial and had time to use it.

A second said that the government did not disclose that child pornography was found on a computer belonging to former Cmdr. Jose Sanchez, who had pleaded guilty, cooperated with the government and was supposed to testify. However, after defense lawyers learned during the trial of the alleged pornography, the government abruptly decided not to put him on the stand — after Sammartino said she would issue another instruction telling the jury of the failure to disclose.

Sammartino ruled that because Sanchez was never called, there was no damage done to the defendants’ case.

The latest news, as soon as it breaks.

Get our email alerts straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.