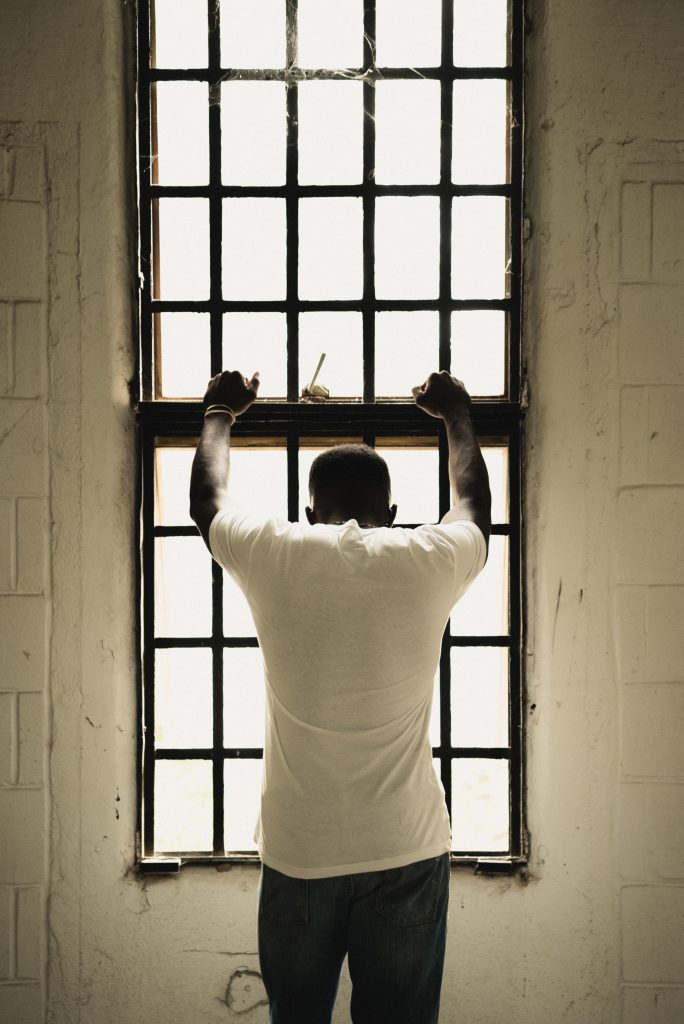

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines the term “solitary confinement” as “the state of being kept alone in a prison cell away from other prisoners.” That definition is similar to how the National Commission on Correctional Health Caredefines the term: “Solitary confinement is the housing of an adult or juvenile with minimal to rare meaningful contact with other individuals.”

It’s true that prison officials use the practice as a punishment or for safety purposes in response to dangerous situations. But, as the Vera Institute of Justice has explained, prison officials also use solitary confinement “as a broad catch-all to respond to a wide range of behaviors, including low-level and nonviolent misbehaviors, and to manage vulnerable populations, including those experiencing symptoms of mental illness or requiring protective custody.”

According to a one-of-a-kind study led by Yale Law School from earlier this year, the number of people in solitary confinement or, as prison officials might say, “restrictive housing,” in the U.S. is between 41,000 and 48,000, a violation of the minimum standards set forth by the United Nations, which considers isolation in prison as a form of torture.

Does solitary confinement help with public safety?

No. As Robert J. Cramer, Ph.D., explains in this article for Psychology Today, “[s]olitary confinement doesn’t work.” “The body of evidence shows absolutely no support that solitary confinement reduces violence or improves any of these outcomes,” Dr. Cramer writes. “At best, solitary confinement does not make violence risk worse; however, some data exist suggesting solitary confinement may actually make violence more likely during and after institutionalization.”

Or, as Tiana Herring put it in this article for Prison Policy, “Correctional officials often defend their frequent use of solitary confinement as an effective means of maintaining order and deterring violence and gang activity.” “But,” she continues, “this reliance on solitary ignores the abundance of studies demonstrating the harmful and often long-lasting effects it wreaks on the human mind and body.”

Why do we continue to use solitary confinement?

Even though the science seems clear in demonstrating that solitary confinement hurts more than it helps, the U.S. continues to use it at a record-high rate. That record-high rate is attribute, at least in part, to strong advocacy for the practice by the enforcement arm of the government, including police, prosecutors and jail and prison guards. In fact, some of those government agents aren’t even willing to accept the existence of the term “solitary confinement,” much less the harms associated with the practice.

For instance, according to the New York City Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association, Inc., the self-labeled “second-largest municipal jail union in the nation and the second-largest law enforcement union in New York City,” “corrections professionals” don’t even use the term “solitary confinement.” Instead, they claim, “[t]hat term, and those like it, is a well chosen demonizing expression created by the prison reform movement geared at evoking a reaction.”

The Takeaway:

At this point, practically all of the available research and studies demonstrate that solitary confinement doesn’t work. If anything, it seems that it makes things worse. Yet, in the U.S., we continue to use the practice at a record-high rate. In fact, according to the second-largest jail union in the country, “corrections professionals” don’t even acknowledge that the term “solitary confinement” exists.